FIG PUBLICATION NO. 45Land Governance in Support of

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| This publication as a .pdf-file (39 pages - 1,384 KB) |

2. Executive Summary

Global Challenges

Land Governance Supporting the Global Agenda

The Conference

Conclusions

4. Conference Profile

Setting the Scene

5. Land Governance

Supporting the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)

Responding to the New Challenges

6. Conference Highlights and the Way Forward

Theme 1: Land Governance for the 21st Century

Highlights of the Conference

The Way Forward

Theme 2: Building Sustainable and Well Governed Land

Administration Systems

Highlights of the Conference

The Way Forward

Theme 3: Securing Social Tenure for the Poorest

Highlights of the Conference

The Way Forward

Theme 4: Making Land Markets Work for All

Highlights of the Conference

The Way Forward

Theme 5: Improving Access to Land and Shelter

Highlights of the Conference

The Way Forward

Theme 6: Land Governance for Rapid Urbanisation

Highlights of the Conference

The Way Forward

7. Appendices

Conference Programme

Reference to Proceedings

This publication is a result of the joint FIG-World Bank Conference on “Land Governance in Support of the Millennium Development Goals: Responding to New Challenges” held at the World Bank Headquarters in Washington DC, 9–10 March 2009. It includes a report identifying the highlights of the conference, the ways forward, and also a declaration produced as a conclusion of the conference.

The organisers wish to thank all who participated, contributed, supported and encouraged this conference. The support and funding providing by the ESRI, Trimble, The Dutch Kadastre, GTZ, Leica, and ITC are gratefully acknowledged. Finally, we wish to convey our sincere gratitude and thanks to all the delegates who travelled from all parts of the world to attend this conference and participated so actively and enthusiastically.

This report will be tabled at the FIG Congress in Sydney 11–16 April 2010 and at the World Bank Land Conference in Washington 26–27 April 2010. This should assist national governments and land professionals to develop and improve appropriate land governance in support of the Millennium Development Goals and to address the new challenges.

| Stig Enemark FIG President |

Klaus Deininger Lead Economist, World Bank |

World Bank Headquarters, Washington D.C., USA

The 21st century has dawned with the world facing global issues of climate change, critical food and fuels shortages, environmental degradation and natural disaster related challenges as today’s world population of 6.8 billion continues to grow to an estimated 9 billion by 2040 when over 60% will be urbanised. This is placing excessive pressure on the world’s natural resources.

The eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) form a blueprint agreed to by all the world’s countries and the world’s leading development institutions to support the mitigation of these global issues. The first seven goals are mutually reinforcing and are directed at reducing poverty in all its forms. The last goal – global partnership for development – is about the means to achieve the first seven. These goals are now placed at the heart of the global agenda.

Land governance is about the policies, processes and institutions by which land, property and natural resources are managed. This includes decisions on access to land, land rights, land use, and land development. Land governance is basically about determining and implementing sustainable land policies and establishing a strong relationship between people and land. Sound land governance is fundamental in achieving sustainable development and poverty reduction and therefore a key component in supporting the global agenda, set by adoption of the MDGs. The contribution of the global community of Land Professionals is vital.

Measures for adaptation to climate change will need to be integrated into strategies for poverty reduction to ensure sustainable development. The land management perspective and the role of the operational component of land administration systems therefore need high-level political support and recognition.

The conference involved 200 invited international experts and was jointly organised by FIG and the World Bank with the overall objective to emphasise the important role of Land Governance in implementing the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and responding to new global challenges. The responses are categorised into the following six conference themes:

The Land Governance for the 21st Century theme focused on adapting and improving our approaches to land governance to be more sensitive to and supportive of these new challenges and to make stakeholders fully aware of the incentives to adopt this paradigm shift. Good land governance must not only control and manage the effective use of physical space, but must also be holistic to ensure sound economic and social outcomes. The World Bank’s land governance assessment framework provides countries with an opportunity to assess and improve their current approaches to meet these global challenges, especially climate change. Land governance must be further democratised by developing tools for all stakeholders to increasingly participate and form partnerships in policy formulation, implementation and monitoring all within more realistic timeframes. The international community must also provide guidance and contract evaluation tools and services to mitigate the risks for countries negotiating international land acquisition contracts – the so called ‘farmlands grab.’

The Building Sustainable, Well Governed Land Administration Systems (LAS) theme emphasised the role of LAS in providing the infrastructure for implementing land policies and land management strategies in support of sustainable development. LAS must evolve and must be aligned with the current needs of a country through the requirements defined in a land policy framework. LAS are most effective when managed as a business and have a sustainable funding model based on a robust business case. Early investments in positioning infrastructures can realise significant benefits in a wide range of land applications. However, it is estimated that LAS are only fully operational and work reasonably well in about 30 and mainly western countries. Thus, the fundamental support of LAS in achieving the MDGs is of serious concern.

The Securing Social Tenure for the Poorest theme addressed the need of securing tenure for the rural poor and the 1 billion slum dwellers world-wide; reaching 1.4 billion by 2020 if no remedial action is taken. Conventional cadastral and land registration systems cannot supply security of tenure to the vast majority of the low income groups. It is imperative that we develop innovative new approaches that can be scaled to solve this escalating global issue. It is essential to establish good land policies that achieve equitable land distribution and fair laws that are pro-poor. However, new pro-poor, scalable tools to achieve security of tenure for the slum dwellers need to include social and customary tenure approaches and the corresponding LAS should adopt the Social Tenure Domain Model that is currently being developed in a cooperation between FIG, ITC, UN-HABITAT and the World Bank.

The Making Land Markets Work for All theme identified ways of breaking down the barriers to land markets access. In many countries certain land rights are not a tradable commodity, such as customary land rights, allodial lands, religious lands etc., and access to the market may be restricted by financial, corruption, social or informational reasons. The sub-prime mortgage crisis and the unbundling of property rights into complex commodities have also exposed high risk groups and in many cases poor people have been left landless. Fairer and more equitable access to the land sales and rental markets can be achieved through an effective primary land market, the provision of homeowners guarantee funds, government co-ordination of social housing, market transparency to reduce corruption and the introduction of monitoring tools to evaluate the performance of the functioning of land markets, e.g. the World Bank ‘Doing Business Reports.

The Improving Access to Land and Shelter theme focussed on interventions to support the increasing number of citizens who do not have access to land and adequate shelter. This exclusion is caused, in many cases, by structural social inequalities, inheritance constraints, conflicts, and often land administrations systems are ineffective and expensive for the end user. Land reform is unfinished business and interventions are still necessary to reduce the structural inequalities since market forces will not naturally alleviate the situation. The forced migration of people in conflict situations, or the result of disasters, causes significant access issues to land and shelter. Longer term measures for housing and land and property rights need to be put in place to support social stability. Finally, more effective gender responsive land tools are required to widen women’s access to land. All these interventions need to be applied within the broader context of economic growth and poverty reduction policies.

The Land governance for Rapid Urbanisation theme reviewed responses to this global phenomenon that will result in 60% of the world’s population being urbanised by 2030. This incredibly rapid growth causes severe ecological, economical and social problems, with over 70% of the growth in developing countries currently happens outside of the formal planning process. However, urbanisation with the continuing concentration of economic activities in cities is inevitable and generally desirable. Increasing economic density remains the objective for all areas at different stages of urbanisation. Due to the significant dynamics of urbanisation, urban planning and public infrastructure provision tends to be reactive rather than a guide to development. It is therefore essential that appropriate priorities for policies are set at different stages in urbanisation, essentially providing the elements of an urbanisation strategy that conforms to the reality of growth and development.

Effective and democratised land governance is at the heart of delivering the global vision of our future laid out in the MDGs. However, the route to this vision is rapidly changing as a series of new environmental, economic and social challenges pervade and impact every aspect of our lives. Land Professionals have a vital role to play and we must understand and respond quickly to this on-going change. Our approaches and solutions across all facets of land governance and associated Land Administration Systems must be continually reviewed and adapted so that we can better manage and mitigate the negative consequences of change. Central to this is our response to climate change and food security.

Washington D. C., USA.

FIG–World Bank Declaration on Land Governance in Support of the Millennium Development GoalsAll countries have to deal with governing their land. They have to deal with the governance of land tenure, land value, land use and land development in some way or another. A country’s capacity may be advanced and combine all the activities in one conceptual framework supported by sophisticated ICT models or, more likely, capacity will be involved in very fragmented and basically analogue approaches. Effective systems for recording various kind of land tenure, assessing land values and controlling the use of land are the foundation of efficient land markets and sustainable and productive management of land resources. Such systems should be based on an overall land policy framework and supported by comprehensive land information and positioning infrastructures. Sustainable land governance should:

As an outcome of the conference, some key recommendations have emerged. These are argued in more details in this report in terms of the way forward within the six themes of the conference. |

The conference was jointly organised by FIG and the World Bank with the overall objective to emphasise the important role of Land Governance in implementing the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and responding to new challenges such as Climate Change and Urban Growth. The conference demonstrated how FIG and the World Bank are working in parallel to achieve these global aims.

The conference aimed to illustrate the far reaching impact of land institutions, highlighting successes, failures and remaining challenges for improving land, and identify resources and measures that can be drawn upon by interested parties.

The conference was recognised as a major milestone in tackling global land issues and was attended by around 200 invited internationals experts within the land sector representing governments, UN agencies, development agencies, professionals, academia and the private sector.

The conference was divided into six themes:

About 80 papers were presented in 20 sessions. Proceedings are available on both the FIG and the World Bank websites and the full programme of the conference is presented in Appendix 1.

Setting the Scene

|

Arguably sound land governance is a key to achieve sustainable development and to support the global agenda as set by adoption of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Land governance is about the policies, processes and institutions by which land, property and natural resources are managed. This includes decisions on access to land, land rights, land use, and land development. Land governance is basically about determining and implementing sustainable land policies.

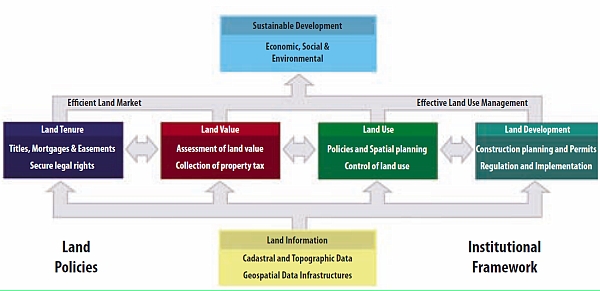

Sound land management requires operational processes to implement land policies in comprehensive and sustainable ways. Many countries, however, tend to separate land tenure rights from land use opportunities, undermining their capacity to link planning and land use controls with land values and the operation of the land market. These problems are often compounded by poor administrative and management procedures that fail to deliver required services. Investment in new technology will only go a small way towards solving a much deeper problem: the failure to treat land and its resources as a coherent whole. Such a global perspective for land governance and management is shown below (Enemark).

A Global Land Management Perspective.

Land governance and management covers all activities associated with the management of land and natural resources that are required to fulfil political and social objectives and achieve sustainable development. This relates specifically to the legal and institutional framework for the land sector. The operational component of the land management concept is the range of land administration functions that include the areas of: land tenure (securing and transferring rights in land and natural resources); land value (valuation and taxation of land and properties); land use (planning and control of the use of land and natural resources); and land development (implementing utilities, infrastructure, construction planning, and schemes for renewal and change of existing land use). All of these are essential to ensure control and management of physical space and the economic and social outcomes emerging from it.

Land Administration Systems (LAS) are the basis for conceptualising rights, restrictions and responsibilities. Property rights are normally concerned with ownership and tenure whereas restrictions usually control use and activities on land. Responsibilities relate more to a social, ethical commitment or attitude to environmental sustainability and good husbandry. In more generic terms, land administration is about managing the relations between people, policies and places in support of sustainability and the global agenda set by the MDGs.

Good governance is generally recognised as critical for sustainable growth and poverty reduction. At the same time, the impact of the legal and institutional frameworks that determine how land related issues are managed has only recently been fully appreciated.

The eight MDGs form a blueprint agreed to by all the world’s countries and the world’s leading development institutions. The first seven goals are mutually reinforcing and are directed at reducing poverty in all its forms. The last goal – global partnership for development – is about the means of achieving the first seven.

These goals, as shown in figure below, are now placed at the heart of the global agenda. To track the progress in achieving the MDGs a framework of targets and indicators has been developed. This framework includes 18 targets and 48 indicators enabling the ongoing monitoring of the progress that is reported on annually.

|

Goal 1: Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger Goal 2: Achieve universal primary education Goal 3: Promote gender equality and empower women Goal 4: Reduce child mortality Goal 5: Improve maternal health Goal 6: Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases Goal 7: Ensure environmental sustainability Goal 8: Develop a Global Partnership for Development |

The Eight Millennium Development Goals.

The MDGs represent a wider concept or a vision for the future, where proper land governance is central and vital and where the contribution of the global community of land professionals is fundamental. This relates to the areas of providing the relevant geographic information in terms of mapping and databases of the built and natural environment, and also providing secure tenure systems, systems for land valuation, land use management and land development. These aspects are all key components in achieving the MDGs.

The key challenges of the new millennium are clearly listed already. They relate to climate change; food shortage; urban growth; environmental degradation; and natural disasters. These issues all relate to governance and management of land.

The challenges of food shortage, environmental degradation and natural disasters are to a large extent caused by the overarching challenge of climate change, while the rapid urbanisation is a general trend that in itself has a significant impact on climate change. Measures for adaptation to climate change must be integrated into strategies for poverty reduction to ensure sustainable development and for meeting the MDGs.

The UN secretary general Ban Ki-moon has stated that “climate change is the defining challenge of our time”. He said that ”combining the impacts of climate change with the current global financial crisis we risk that all the efforts that have been made by countries to meet the Millennium Development Goals and to alleviate poverty, hunger and ill health will be rolled back. It is clear that those who suffer the most from the increasing signs of climate change are the poor. Those that contributed the least to this planetary problem continue to be disproportionately at risk.”

On the other hand the global challenge of climate change also provides a range of opportunities. The Executive Director of UN-Habitat Dr. Anna Tibaijuka has said (Urban World, March 2009) that “prevention of climate change can be greatly enhanced through better land–use planning and building codes so that cities keep their ecological footprint to the minimum and make sure that their residents, especially the poorest, are protected as best as possible against disaster”. This also relates to the fact that some 40 percent of the world´s population lives less than 100 km from the coast mostly in big towns and cities. A further 100 million people live less than one metre above mean sea level.

The Director General of UN-FAO, Jacques Diouf, has said (World Summit of Food Security, November 2009) that “in support to climate change mitigation and adaptation policy, the FAO created a National Forest Programme Facility in 2002’”. The initiative is presently supporting 70 countries and regional organisations. In 2008 FAO established the United Nations Collaborative Programme on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing Countries followed by a global forest monitoring system in support of carbon accounting and payments.

Adaptation to and mitigation of climate change, by their very nature, challenge governments and professionals in the fields of land use, land management, land reform, land tenure and land administration to incorporate climate change issues into their land policies, land policy instruments and facilitating land tools. More generally, sustainable land administration systems should serve as a basis for climate change adaptation and mitigation. The management of natural disasters resulting from climate change can also be enhanced through the creation and maintenance of appropriate land administration systems. Climate change increases the risks of climate-related disasters, which cause the loss of lives and livelihoods, and weaken the resilience of vulnerable ecosystems and societies.

In short, the linkage between climate change adaptation and sustainable development should be self evident. Measures for adaptation to climate change will need to be integrated into strategies for poverty reduction to ensure sustainable development. The land management perspective and the role of the operational component of land administration systems therefore need high-level political support and recognition.

At the start of the 21st century the world is facing critical global food and fuels shortages, climate change, urban growth, environmental degradation and natural disaster related challenges as today’s world population of 6.8 billion continues to grow to an estimated 9 billion by 2040. This is placing inordinate pressure on the world’s natural resources.

The surge in the price of key food products such as rice and wheat, which last year hit record highs, sparked food riots in many countries. Food security has become a key global challenge. In response to the crisis, many countries and private corporations are exploring new ways of safeguarding their supplies of natural resources; especially crops for food and bio-fuels. A global search is now underway to identify ‘underutilised’ land in areas suitable for agricultural production and to acquire the land for large scale agricultural production. Significant areas of land in Africa, India and South America have now been bought or leased to foreign countries or corporations – the so called ‘farmlands grab.’

Although these investments attract capital along with technology and market knowledge to potentially improve agriculture, there are many inherent concerns that are not always covered in the associated contracts: agricultural produce is directly exported from countries with a food deficit; there is no ‘unused’ land and in many cases local people are taken off the land with little compensation; the easiest land to acquire is government land and the benefits normally go to the political elite rather than the local people; large scale agriculture does not employ significant numbers of local people; and much common land, such as grazing land, is targeted and lost. It is increasingly relevant that we strengthen land governance across the globe to ensure that all stakeholders understand their roles and responsibilities in managing land, property and natural resources within a sustainable and equitable framework.

The key challenges of the new millennium are all interconnected, with many being perpetrated by climate change. Our understanding of the problems and the formulation of potential solutions will only be achieved through a holistic approach involving collaboration across the professions. Land professionals have a key role in this alliance through the effective management of spatial information related to the built and natural environments and the application of good land governance to help mitigate the damaging impacts on our world and society. We need to adapt our approaches to be more sensitive to and supportive of these new challenges and make stakeholders fully aware of the incentives for adopting this paradigm shift. Good land governance must not only control and manage the effective use of physical space, but must also ensure sound economic and social outcomes.

New Zealand.

1. Adapt land governance to be more supportive of our global challenges

Effective and democratised land governance is at the heart of delivering the global vision of our future laid out in the MDGs. However, the route to this vision is changing as a series of new environmental, economic and social challenges spread through and impacts every aspect of our lives. The degree of change and uncertainty in our world is increasing. As land professionals we must understand and respond quickly to this on-going change. Our approaches and solutions across all facets of land governance must be reviewed and adapted so that we can better manage and mitigate the negative consequences of change. Central to this is our response to climate change.

2. Adopt the world bank assessment framework to improve current approaches to land governance

Poor land governance has far-reaching economic and social consequences: lack of inward investment and economic growth; limited poverty reduction; increased deep-rooted conflicts; significant corruption and land grabbing. This all leads to social instability. The increase in population and the growing demand for land driven by food security and biofuels needs will increase the value of land. These trends will worsen the current land related problems unless land governance can be improved to cope with these new challenges. The World Bank’s land governance assessment framework provides countries with an opportunity to assess and improve their current approaches to land governance. This should be an on-going process and countries should transparently publish their assessment results in the public domain. The assessment framework should also be regularly updated to ensure that the land governance we aspire to is increasingly relevant to the new millennium, global challenges, especially climate change.

3. Increase participatory tools to build partnerships and further democratise land governance

As the visibility and role of land governance strengthens in the wider policy arena, it is essential that we further democratise land governance by developing tools for all stakeholders to increasingly participate and form partnerships in policy formulation, implementation and monitoring. For example, land policy reforms contribute more fully to poverty reduction and sustainable development when closely related to processes that empower civil society, especially poor men and women, in decision-making processes. And more effective aid is provided when development partners are involved early in planning policy implementation. These tools need to be shared across the international community. However, secure land rights are fundamental in minimising arbitrary dispossession and maximising local benefit.

4. Provide contract evaluation tools to safeguard nations from inappropriate large scale, international land acquisitions

The ethical basis and the economic and social impacts of the increasing number of large scale, international land acquisitions, driven by food security and the scramble for biofuels, need to be questioned. Large areas of relatively unproductive land across the globe are being leased or sold to foreign governments and corporations for large scale agricultural production. This mostly involves government land and commons. The contracts rarely provide benefits to local people and there are major concerns about the environmental and social impacts, especially when agricultural produce is being exported from countries with food deficits. Too often these contracts are signed without sufficient due diligence on their affect on the ground. The international community needs to provide contract evaluation tools and services to countries negotiating international land acquisition contracts.

5. Adopt realistic timeframes to ensure more effective land policy implementations

Over the past decade around 15 African nations have successfully formulated their National Land Policies through participative and inclusive approaches. However, their corresponding record in implementing their National Land Policies is less successful. This lack of success derives, in many cases, from overly ambitious implementation timescales and insufficient institutional and legal reforms to support the new land policies. Countries need to adopt a more realistic and incremental approach to implementation, where small successful steps will build optimism and effectively change the power relationships over land issues in the country.

Ghana.

Land Administration Systems (LAS) provide the infrastructure for implementing land policies and land management strategies in support of sustainable development. This infrastructure includes the institutional arrangements, a legal framework, processes, standards, land information, management and dissemination systems, and technologies required to support allocation, land markets, valuation, control of uses, and development of interests in land. LAS are dynamic and evolve to reflect the people-to-land relationships, to adopt new technologies and to manage a wider and richer set of land information.

The LAS is the fundamental infrastructure that underpins and integrates the land tenure, land value, land use and land development functions of land administration to support an efficient land market that fully demonstrates sustainable development. The land information should form part of a wider spatial data infrastructure (SDI) to ensure its wider use in a range of social, economic and environmental applications and services. However, it is estimated that LAS are only fully operational and work reasonably well in about 30 and mainly western countries. Thus, the fundamental support of LAS in achieving the MDGs is of serious concern.

To support an inclusive approach, a ‘well governed’ LAS is an infrastructure that is managed in such a way that the products and services are of the appropriate quality level, affordable, easy to use, support short transaction times and are fully transparent. The delivery of this outcome requires a combination of business and technical skills. The sustainability of LAS is enhanced when supporting legal frameworks define a view of the role and function of LAS in the implementation of the land policy; especially for land related laws, such as land law, registration law, fiscal law, land use law etc.

The LAS must operate within and respond to the requirements within a land policy framework. Recent World Bank research reports indicate ‘land tenure’, ‘land markets’ and ‘socially desirable land use’ are main drivers for a land policy. These three goals comprise a whole range of instruments, such as the forms of land tenure and how they are recognised in the country, the level of land tenure security that should be provided, the interventions in the land and credit market that are beneficial, the nature of land use planning, state land management and land acquisition for the public good, use of land taxation for budget generation and land use steering, valuable land reform options and workable solutions for land conflicts. The land policy is not isolated as it must be embedded in the wider political agenda of poverty eradication, sustainable agriculture and housing, protection of the vulnerable people, equity of social groups and women, rapid urbanisation, food security, climate change and slum upgrading etc.

It is crucial to understand that LAS can never be an end in themselves; their nature is to serve society, whatever that society currently looks like. For many countries this is definitely a break with the past, because elements of LAS, such as land registration and cadastral boundary surveying, are considered historically as an instrument of the colonial or otherwise ruling powers to securing their own land rights. ‘Sustainable’ land administration systems are therefore systems that serve society well, by providing effective sets of products and services that are fully inclusive to meeting demand now and in the future. This includes the poor who are currently excluded from participating in many countries.

1. Create a land policy framework to let the LAS function more effectively

LAS products and services must be aligned with the current needs of a country. These requirements must be defined in land policy, describing how governments intend to deal with the allocation of land and land related benefits and how LAS are supposed to facilitate the implementation. Such implementation includes the rules for land tenure and land tenure security, the functioning of the land market, land use planning d development, land taxation, management of natural resources, land reform etc.

2. Adopt a business led approach to deliver better managed LAS

Although based on scientific concepts, methods, and principles, land administration is a business process that should be managed as a business. Therefore, land administrators need to be acquainted with business administration knowledge, safeguarding good process design and workflow management, performance monitoring and daily financial management. Managers need to have knowledge of both professional matters and ICT matters, to guarantee good alignment between business objectives and ICT support. A sharp eye for customer relations is a prerequisite for sound performance, and a sufficient justifier for investments. Essentially, land administration functions need to be transparent and free from corruption.

3. Invest early in positioning infrastructures to realise benefits in a wide range of land applications

Historically, national triangulations have formed the base for consistency in land surveying. Nowadays, these positioning infrastructures constitute not only the base for land surveying and place based land information in all its forms, but the infrastructures also supports a wide range of land applications. The performance of LAS has proven to be enhanced strongly by applying appropriate ICT-tools, including satellite imagery, aerial photographs and GNSS. Early investments in this positioning infrastructure are crucial.

4. Promote evidence of LAS to support economic growth and poverty reduction

LAS can be sustainable when the solution fulfils its expected function by users on a continuous and satisfying basis. Good quality management procedures continually safeguard the relevance of the LAS in current and changing times. Maintenance of the records and underlying information, as a minimum, is of paramount importance and financial arrangements should allow for registers and maps to reflect the situation on the ground day by day. Without appropriate funding arrangements this is difficult. Therefore the development of the LAS must be based on a realistic business model. Although investments in land administration are usually justified through qualitative arguments, more attention should be paid to providing robust quantitative evidence such as contributions to economic growth and poverty reduction that are of direct interest to politicians.

Chile.

Today there are many rural poor and around 1 billion slum dwellers world-wide. UN-Habitat estimates that if the current trends continue, the slum population will reach 1.4 billion by 2020, if no remedial action is taken. These astonishing figures are fuelled by the rush to the cities and over half of the world’s population today live in urban areas. Current trends predict the number of urban dwellers will keep rising, reaching almost 5 billion in 2030 where 80% will live in developing countries.

In this perspective, where one of every three city residents lives in inadequate housing with few or no basic services, it becomes urgent to focus on informal settlement and to support the MDG 7, target 11 to have improved the lives of least 100 million slum dwellers by 2020.

Most of the urban poor do not have secure tenure within these large informal settlements. Securing formal recognised rights to land and housing in urban areas will generally give people access to basic services and it may also help them to access legal and financial services to raise capital to invest. It is therefore essential that we put in place good land policies that focus on achieving equitable land distribution and fair laws that take into account the interests of the poor.

Conventional cadastral and land registration systems cannot supply security of tenure to the vast majority of the low income groups. It is imperative that we develop innovative new approaches that can be scaled to solve this escalating global issue. Land Administration Systems will have to be modified to accommodate a wider range of levels of tenure security and integrate customary systems of tenure. New low cost surveying tools are emerging and need to be integrated into cadastral surveying processes. The understanding that enjoying secure land tenure is also a matter of human rights and social justice, encourages unconventional solutions, whether it regards forms of land rights, levels of security or land administration tools. The Land Professional has a key role to play in delivering these more appropriate tools.

Many communities across the world have land rights under communal or customary systems that are often not secure in law. Land and resource rights include both strong individual and family rights to residential and arable land and access to a range of common property resources such as grazing, forest and water. There is group oversight and rules to keep land within the group that are normally derived from customary norms and principles. The lack of legal security can lead to vulnerability in practice, e.g. when predatory states re-allocate land to foreign investors.

The policy challenge is to decide what kinds of rights, held by which categories of claimants, should be secured under tenure reform and integrated into a Land Administration System. This is complex since customary tenure regimes are not static and traditionbound, but dynamic and evolving and the associated boundaries are often ambiguous, or flexible or overlapping. The diversity, imprecision and flexibility makes it difficult to codify them and provide them with legal definition. However, this is essential to provide this section of society with a potential route out of poverty and reduced threats of eviction.

1. Adopt a continuum of rights approach to deliver faster and wider security of tenure to the poor

UN-HABITAT’s ‘continuum of rights’ recognises that rights to land and resources can have many different forms and levels. Just as ‘land tenure’ has the notion of a statutory land right, other forms of land rights, such as anti-eviction ‘right’, group tenure etc., refer to the recognition of somebody’s land possession within the social community and can be called ‘social tenure’. Land professionals must include ‘social tenure’ in their scope of professional attention and deliver more social tenure oriented solutions.

2. Include customary tenure in Land Administration Systems to reduce vulnerability

The diversity, imprecision and flexibility of communal or customary systems makes it difficult to provide them with legal definition. However, it is essential that these social groups are provided with appropriate forms of tenure security within Land Administration Systems that do not restrict their ongoing evolution. These sections of society, especially in rural areas, need a potential route out of poverty and reduced threats from farmland grabs, for example.

3. Adopt the Social Tenure Domain Model to support pro-poor Land Administration System solutions

Traditionally, the technology supporting Land Administration Systems uses models and terminology that is aligned with formal, legal systems, making it impossible to adequately support social tenure systems with pro-poor technical and legal tools. However, the development of a solution to this problem is being supported by FIG called the Social Tenure Domain Model (STDM), originally developed as the Core Cadastral Domain Model (CCDM). The STDM is a tool to deal with the kind of social tenure that exist in informal settlements (and also in areas based on customary tenure) that cannot be accommodated in traditional Land Administration Systems. It is planned to provide this ISO standards based solution as free and open source software and should be available as a tool for local communities as well as public authorities.

4. Develop pro-poor and gender sensitive land tools to improve the lives of the poor

UN-Habitat has an agenda around the Global Land Tool Network (GLTN) that aims to facilitate the attainment of the MDGs through improved land management and tenure tools for poverty alleviation and the improvement of the livelihoods for the poor. All Land Professionals are encouraged to support and contribute to this effective initiative to alleviate the current level and scale of poverty.

Nairobi, Kenya.

The land market, more precisely the market in property rights to land, is not always characterised as a perfect market, where demand and supply are brought to the most efficient use by the ‘invisible hand’ of the market mechanism. In many countries certain land rights are not a tradable commodity, such as customary land rights, allodial lands, religious lands etc. Even when land rights are fully tradable, the market can still be far from perfect since access to that sales market may be restricted by financial, corruption, social or informational reasons.

Many people cannot afford an initial investment in land and there is growing interest in the functioning of the land rental market. Agricultural leases and residential rents are easier to pay through regular income generation, while buying needs a lot of savings or credit facilities. There are also many social obstacles to land market participation as people might not be familiar with how the market functions through illiteracy and missing education, for example. Lack of transparency and information and complex regulations also creates obstacles. The resulting restrictions mostly disadvantage of the poor, while being at the advantage of the powerful elites. This then results in unequal land possession, and at worse, land grabbing and speculation.

Markets in land rights seldom exist in customary areas, where ownership of land is vested in the community. Allocation of use rights is de facto and executed by chiefs, family heads or even the President of the nation. Scarcity of lands, growing population, and mobility of people lead in many cases to a demand for individual land rights in these commonly owned lands. In addition, land claims are increasingly coming from governments or from project developers and examples show that chiefs of representatives of collectives do not always understand that they act on behalf of the community and not for themselves. This erosion of customary areas is creating the ‘new tragedy of the commons’ symbolising the land grab in these areas.

Participating in the market requires a certain purchase power. This might come from savings, but it might take a long time before people are able to buy property. Land and houses are particularly suitable for serving as collateral for a loan. However, as the subprime mortgage crisis in the US revealed, inappropriate loans being provided to high risk groups can lead to foreclosures and distress sales, leaving poor people landless. The financial services sector and governments have a major responsibility to set up regulatory frameworks to reduce the risk of re-occurrence.

Land markets need to be accessible by all and supported by land information systems that provides transparency in information about ownership rights and associated transactions and an institutional framework that delivers simple, affordable and efficient land administration services. In many countries the World Bank ‘Doing Business Reports’ facilitate the streamlining of procedures to make transactions simpler, quicker and cheaper.

However, the concept of property is rapidly evolving from simple ownership or use, towards complex commodities generated by unbundling property rights, into separate tradable mineral rights or carbon credits, for example. This ‘unbundling’ of rights leads to speculative collateralised debt obligations and, as the recent financial crises has highlighted, stronger regulation is required across the land and financial services sectors.

The Way Forward

1. Improve primary land delivery to boost land markets

In many countries the trade in land rights between parties (secondary land market) can only develop after the delivery of land to citizens by the government (primary land market). When the primary market does not function well, the secondary market cannot effectively develop causing informal or illegal land occupation, slums and illegal land markets. This land delivery is hampered by long lasting procedures, complex regulations, and weak government structures, for example. Therefore, an effective primary land market is a prerequisite for any market improvement.

2. Don’t leave social housing to market forces

A consequence of a poorly functioning primary land market is the lack of

social housing supply. When the land market does not work for certain groups

in society, especially the poor, the principles of institutional economics

dictate that governments should assume responsibility for providing social

housing. The allocation of houses in this situation should not be left to

the land market, but to social housing organisations. Governments should

meet their responsibility to

coordinate social housing.

3. Guarantee homeowners funds to protect the poor

When secured credit is used for production purposes, such as buying livestock, seeds and fertilizers, opportunities for capitalising on property might exist, on the understanding that the loans can be reasonably paid back. Some countries offer state guarantees in the form of homeowners guarantee funds, which aim at protecting the poor against unbearable debts when, unfortunately, loans cannot be paid back and the property might be forcedly sold against liquidity value. The development of such homeowners guarantee funds is highly advisable.

4. Reduce corruption through transparency of markets and incorruptible land professionals

Corruption investigations have revealed that the land sector is prone to significant grand and petty corruption. Transparency is the key to fair and equitable access to the land sales and rental market for all. A high standard of ethics in the work of land administrators is also a prerequisite to combat bribing and land grabbing. Therefore, the FIG developed codes of conduct should be adopted by national and local land professional associations.

5. Offer fair compensation when the State acquires land and evicts people

Often the poor suffer from unfair acquisition of land by the State. Although the justification for land taking might be legitimate, private right holders should be treated fairly when losing their land rights. In many circumstances, local government officials play an important role in offering fair compensation for people to be evicted and land professionals should develop transparent procedures for land acquisition with fair compensation mechanisms.

6. Introduce monitoring tools to measure the effective functioning of the land markets

Many countries are simplifying the number of procedures and reducing the time and costs involved in transactions in the land market and are realising economic benefits. Monitoring tools need to be introduced to evaluate the performance of the functioning of the land market. An example of an existing tool is the World Bank ‘Doing Business Reports’. Land administration systems also need to support both traditional and modern communal systems to ensure that they are protected within the market context.

Mozambique.

Mexico.

An increasing number of citizens do not have either permanent or temporary access to land and adequate shelter. This exclusion is caused, in many cases, by structural social inequalities, inheritance constraints, conflicts, non pro-poor and pro-gender land policies and land administrations systems that are ineffective and expensive for the end user. Without a range of appropriate interventions being applied within the broader context of economic growth and poverty reduction policies, social exclusion and poverty will continue to spiral out of control; already 90% of all new settlements in sub-Sahara Africa are slums.

Land markets, or formalisation of existing land rights, in spite of their great flexibility and usefulness to the poor, are not a magical solution for addressing structural inequalities in countries with highly unequal land ownership which reduces productivity of land use and restricts development. To overcome the legacy of such inequality, ways of redistributing assets such as land reform are still needed. While the post war experiences of Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, China showed that land reform can improve equity and economic performance, there are many other cases where land reform could not be fully implemented or even had negative consequences that illustrate the difficulties involved. If, within a broader strategy of poverty reduction, redistributive land reform is found to be more cost-effective in overcoming structural inequalities than alternatives then it needs to be aligned with local needs and complemented by access to political support, managerial ability, technology, credit and markets for the new owners to become competitive.

Every year a significant number of people are forced to migrate from their homes due to conflict situations, evictions or natural disasters. In Iraq, it is estimated that over 5 million Iraqis are currently displaced by violence and the rebels continue to benefit through the lack of a solution. In many countries there are no national policies and associated guidelines that comply with international human rights standards for the eviction of residents of slums and informal settlements. There are examples of evictions involving over 50,000 persons in Africa and these slum residents live in constant fear of eviction. Natural disasters also cause significant displacement of people; the 2004 tsunami displaced over 1.7 million people. Effective and early solutions need to be identified and implemented to solve the housing, land and property issues resulting from these events to enable social and economic stability.

Only 2% of registered land rights in the developing world are currently held by women. Many women have very restricted access rights to land and shelter due to religious, cultural and legal constraints. This situation has been exacerbated by the AIDS epidemic and requires the design of more gender responsive land tools.

The Way Forward

1. Continue effective and sustainable land reform to reduce poverty and inequality

Land is poor people’s main and usually only productive asset. Around 1.5 billion people today have gained farmland due to land reform, resulting in many being less poor, or not poor. However, huge land inequalities remain, or have re-emerged, in many low-income countries; this has been caused by inheritance rather than efficiency and generated inefficient, low-employment farm output. In many developing areas with no, minor, ineffective or incomplete land reform, the poorer half of farming people normally control below 10% of farmland. The impact on the poor is compounded since not only does extreme land concentration increase income inequality, but in developing countries it also reduces farm output and slows growth.

2. Accept that land reform is an on-going process

Land reform interventions are still necessary, in many cases, to reduce the structural inequalities since market forces will not naturally alleviate the situation. Land reform is ‘unfinished business’. The new land reform approaches adopted need to be carefully attuned to their target contexts to attain their goals of reducing poverty and inequality, ensuring output efficiency and growth, and achieving sustainability, stability and legitimacy. Future approaches should be shaped and sensitive to a range of constraints, including the degree of social and land rights inequalities, demographic demand, genders rights and roles, resilience of customary rights, willingness of land owners to cost share, economic affordability of compensation and the capacity of the population to tolerate and support the proposed changes.

3. Address land and shelter access issues up front in conflict and disaster situations

The forced migration of people in conflict situations, or the result of disasters, causes significant short and long term access issues to land and shelter. Even where land is at the centre of the conflict, the emergency, or first phase, is dominated by emergency issues and short-term’ism. It is only in the second, or reconstruction phase, that housing, land and property rights are treated within a medium to long term framework. Too often there is little funding for the second phase by comparison to the first phase. This means that housing, land and property issues in post conflict situations are not always addressed adequately. The approach needs to be improved and longer term measures put in place from the outset and the delivery of solutions accelerated to support social stability.

4. Identify gender responsive land tools to widen women’s access to land

Women’s lack of access to and control over land is a key factor contributing to poverty, especially in the increasing feminisation of agriculture, and needs to be addressed for sustainable poverty reduction. Although the policy statements of almost all donors active in the land and natural resources sector emphasise women’s access to land and many countries also make reference to gender equality in their constitutions, laws relating to property rights do not often give equal status to women. Women’s access to and control over resources is shaped by complex systems of common and civil law as well as customary and religious laws and practices. The practise and perception of a woman’s position in the household, family and community still affects to what extent women can exercise their rights. The challenge now is to translate this political will into action and produce gender equality across the land sector. We need to identify practical solutions, particularly at the grassroots level, that support women’s effective and sustainable access to land and make policy-makers aware of how this can be achieved.

Malawi.

Urbanisation is a major change that is taking place globally. The urban global tipping point was reached in 2007 when over half of the world’s population was living in urban areas; around 3.3 billion people. Although this depends on the definition of ‘urbanisation’, as outlined in the World Bank’s ‘World Development Report 2009, Reshaping Economic Geography’ (World Bank, 2009). It is estimated that a further 500 million people will be urbanised in the next five years and projections indicate that the percentage of the world’s population urbanised by 2030 will be 60%.

This rush to the cities, caused in part by the attraction of opportunities for wealth generation, has generated the phenomenon of ’megacities’ that have a population of over 10 million. There are currently 19 megacities and there are expected to be around 27 by 2020. Over half this growth will be in Asia; the world’s economic geography is now shifting to Asia.

Megacities exert significant economic, social and political dominance over their hinterlands. Mega-urban regions are growing, especially in China (Pearl River Delta) and the US (central east coast) to create clusters of cities or “system of cities” and while not megacities in the traditional form of centre and suburbs, they will form “multi-centre megacities”.

This incredibly rapid growth of megacities causes severe ecological, economical and social problems. It is increasingly difficult to manage this growth in a sustainable way. It is recognised that over 70% of the growth currently happens outside of the formal planning process and that 30% of urban populations in developing countries living in slums or informal settlements, i.e. where vacant state-owned or private land is occupied illegally and used for illegal slum housing. In sub-Saharan Africa, 90% of all new urban settlements are taking the form of slums. These are especially vulnerable to climate change impacts as they are usually built on hazardous sites in high-risk locations. Even in developed countries unplanned or informal urban development is a major issue.

Urbanisation is also having a very significant impact on climate change. The 20 largest cities consume 80% of the world’s energy use and urban areas generate 80% of greenhouse gas emissions world-wide. Cities are where climate change measures will either succeed or fail.

Rapid urbanisation is setting the greatest test for Land Professionals in the application of land governance to support and achieve the MDGs. The challenge is to deal with the social, economic and environment consequences of this development through more effective and comprehensive spatial and urban planning, resolving issues such as the resulting climate change, insecurity, energy scarcity, environmental pollution, infrastructure chaos and extreme poverty.

1. Adapt land governance measures to support evolving cities for economic growth

Urbanisation with the continuing concentration of economic activities in

cities is inevitable and generally desirable. Increasing economic density

remains the objective for all areas at different stages (incipient,

intermediate and advanced) of urbanisation. It is essential that appropriate

priorities for policies are set at different stages in urbanisation,

essentially providing the elements of an urbanisation strategy that conforms

to the reality of growth and development. For example, land markets and land

management policies must be sensitive to the urbanisation stage and adapt

over time to allow the use of the same piece of land to change to

accommodate greater value-added activity. This increase in economic density

needs to be balanced with environmental safeguarding through sustainable

development policies and land policies need to manage and connect megacities

and their hinterlands holistically to maximise the significant

economic and social benefits across the region.

2. Develop urban indicators and new information management approaches to manage complex and dynamic urban environments

Due to the significant dynamics of urbanisation, urban planning and public infrastructure provision tends to be reactive rather than a guide to development. Large portions of cities grow outside of the legislative or development control framework. Lack of information about the informal sector and its dynamics hinders city officials in formulating and implementing an urbanisation strategy and increases the ecological, economic and social problems and risks, such as the threat of disasters. A new set of urban indicators is needed. This should be supported by a new information collection / management paradigm with tools, techniques and policies to monitor and model growth and change across the urban area – all within shorter timeframes than previously accepted.

3. Develop comprehensive and scalable solutions to the shelter problem

Rapid urbanisation challenges the human right of access to land and shelter. Slum upgrading approaches need to be more holistic and integrated into broader slum prevention shelter policies, and appropriate shelter policies. The aim would be to develop off the shelf solutions that are replicable and scalable across major urban areas. The issue needs to be tackled systemically across the city; to include all the cities’ systems from finance, to land, to shelter, to planning, and so on, at a city wide scale, within an over-arching shelter policy rather than in a piecemeal approach. Moving from reactive to preventative approaches is a much needed paradigm shift that must harness the potential of all actors, including the grassroots, the private sector (formal and informal) and a strong decentralised Local Government.

Tokyo, Japan.

Panel at the Closing Session: Joan Kagwanja, Economic Affairs Officer,

UN-ECA, chair of the closing session (left), Paul van der Molen, the

Netherlands, Clarissa Augustinus, UN-HABITAT, Cheryl Morden, IFAD, Jolyne

Sanjak, MCC, Helge Onsrud, Norway and Alain Durand-Lasserve, France and Paul

Munro-Faure, FAO.

FIG Website: http://www.fig.net/pub/fig_wb_2009/

World Bank Website (including video recording of a number of sessions) - click here.

Copyright © The World Bank and the International Federation of Surveyors

(FIG) 2010.

All rights reserved.

International Federation of Surveyors (FIG)

Kalvebod Brygge 31–33, DK-1780 Copenhagen V

DENMARK

Tel. +45 38 86 10 81

Fax +45 38 86 02 52

E-mail: FIG@FIG.net

www.fig.net

Published in English

Copenhagen, Denmark

ISBN 978-87-90907-72-3

Published by

The International Federation of Surveyors (FIG)

DISCLAIMER

The designations employed and the presentation of material in this

publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the

part of the World Bank concerning the legal status of any county, territory,

city or area or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its

frontiers or boundaries regarding its economic system or degree of

development. Excerpts may be reproduced without authorization, on condition

that the source is indicated. Views expressed in this publication do not

necessarily reflect those of the World Bank.

All photos © Stig Enemark

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Editors: Stig Enemark, Robin McLaren and Paul van der Molen

Design and layout: International Federation of Surveyors, FIG

Printer: Oriveden Kirjapaino, Finland

Land Governance in

Support of The Millennium Development Goals

A New Agenda for Land Professionals

FIG / World Bank Conference, Washington DC, USA 9–10 March 2009

Published in English

Published by The International Federation of Surveyors (FIG), 2010

Copenhagen, Denmark

ISBN: 978-87-90907-72-3

Printed copies can be ordered from:

FIG Office, Kalvebod Brygge 31-33, DK-1780 Copenhagen V, DENMARK,

Tel: + 45 38 86 10 81, E-mail:

FIG@fig.net