Making cities wiser - Crowdsourcing for

better decisions

Maarit KAHILA and Anna BROBERG,

Finland

Maarit Kahila Anna Broberg

1)

This paper will be presented at the FIG Working Week 2017 in Helsinki, Finland, 29 May – 2 June.

The paper presents different innovative case studies from Finland and

abroad where Maptionnaire (a leading solution for collecting, analyzing

and discussing resident insight on a map) has been used. Based on the

findings a new public participation model has been drafted.

SUMMARY

The need in urban planning to make knowledge-driven decisions has

spurred the creation of new solutions to gather and utilize insight from

residents. Participatory planning has often been realized through

workshops and during face-to-face encounters, but little of the

knowledge gathered in these situations is of use in further urban

planning and city development. New technological innovations, such as

map-based public participation tools, support gathering information that

matters and makes cities wiser. Interaction with citizens not only

creates information, but supports also learning and innovation building,

and creates trusts.

Technological innovations like Maptionnaire help gather information

that makes cities wiser. Maptionnaire is a leading solution for

collecting, analyzing and discussing resident insight on a map. With the

help of Maptionnaire, various cities have been able to change their

modus operandi. Through these learning processes actors from different

sectors of the city are brought together to create joint understanding

of the possibilities of public participation. Cities have started to

value and use resident input as an equally important part of its

knowledge base for planning. There is a great potential for more

efficient use of participatory tools to make processes smoother and to

save money. Future development work is needed to further facilitate

knowledge transfer from residents to the use of planners and other city

officials.

In our presentation we will present different innovative case

studies from Finland and abroad where Maptionnaire has been used to

support two-way communication in different phases of planning processes.

Based on our findings we will draft a new public participation model

that assist the effective gathering of experiential knowledge from

inhabitants, provide high quality place-based data for various analysis

and informs participants about the stage and goals of the planning

process more innovatively.

INTRODUCTION

Urban planning is constantly seeking a balance between how to

develop and change existing living environments while maintaining their

valuable, existing character. This challenge has become acute in many

growing cities around the world, that share the same concern, how to

shape the existing city structure without reducing the very qualities of

the living environment people value most.

Cities are simultaneously becoming smarter in the ways they use

various sources of digital knowledge that aim to support their growth,

sustainability and usability. To plan cities wisely a broad group of

actors is needed. A central task of a planner is to construct linkages

between the differing actors of civic society and support them by

digital tools and processes. As such, the role of the urban planner in

the smart network society is turning into that of the facilitator who

understands the ongoing complex development patterns. Digitalisation can

enhance participation and integrate the differing voices of plural

society more efficiently. Traditional face-to-face participation methods

can be supplemented by tools utilizing social media and other

information and communication technologies (ICT) like web-based

geographic information systems (webGIS). The central question is not who

organises participation but how the different participation practices –

formal and informal - can be linked together and the information

produced adapted to the planning process.

The more democratic and efficient participatory planning processes

demand that we consider the opportunities for greater public

involvement. With the existing participation methods and procedures like

public hearings, workshops etc. a truly inclusive and effective public

involvement cannot be attained while these methods attract merely

participants that are able and used to express their opinions. Urban

planning practices should be more open to dissenting opinions expressed

by the general public. Though digitalization has brought many new and

inspiring tools to support more extensive participation, the utilisation

and usefulness of them need to be considered carefully in relation to

the specific planning process at hand.

One example of the ongoing digitalisation process emerging in the

participatory urban planning context is the set of webGIS tools such as

public participation GIS (PPGIS) methods. This article introduces one of

these tools, called Maptionnaire, that has been used in the field of

urban planning and that was originally developed in Aalto University in

Finland. We will introduce the tool, give examples of it’s usage in

various stages of the planning process and introduce a heuristic model -

participatory planning support system (PPSS) that emphasises the

usability and benefits of the PPGIS tools during different phases of the

planning process.

1. BACKGROUND OF THE PUBLIC PARTICIPATION GIS (PPGIS)

Researchers and practitioners from different backgrounds have

brought diverse vocabulary to the field of participatory GIS (e.g. Brown

& Kyttä 2014). Location based data collected from informal sources can

be divided roughly into Volunteer Geographic Information (VGI) and data

collected through Public Participation Geographic Information Systems

(PPGIS). VGI is data that is not solicited: it is provided by volunteers

spontaneously. Notable VGI projects include Wikimapia[1]

and OpenStreetMap[2]. In contrast, PPGIS data is

solicited from participants by a particular agency, for example during a

university research project or through participation in a planning

process.

Tulloch (2008) describes PPGIS as a field within geographic

information science that focuses on the ways in which the public uses

various forms of geospatial technologies to participate in different

processes. PPGIS also enables communication to take place on maps and

models in an intelligible visual form to those who have no expertise in

its technical basis (Carver, Evans, Kingston, & Turton, 2001).

Both PPGIS and VGI are related terms that define a process for

gathering and using non-expert spatial information (Brown & Kyttä,

2014). While PPGIS tools are often web-based, originating from the hands

of researchers, VGI tools are generally developed by lay people to

create, assemble, and disseminate voluntarily produced geographic data

(Goodchild, 2007; Hall, Chipeniuk, Feick, Leahy, & Deparday, 2010). VGI

has led to the ‘crowdsourcing’ of spatial information where the

user-generated content is produced by a large group of people through an

online community (Sui, Elwood, & Goodchild, 2012). Although joint

decision making can be understood as an object of crowdsourcing, many

VGI projects have nevertheless targeted rather on geographical

information gathering and visualization on certain topic. In both PPGIS

and VGI, the dimensions of purpose, geographic context, data quality,

sampling approaches, data collection, data ownership and dominant

mapping technology vary depending on the project (Brown & Kyttä, 2014).

Unlike in PPGIS projects the data validation through sampling has not

been in the core of VGI projects. Although both PPGIS and VGI tools can

be considered as tools that can promote data collection from a broad

group of people, this does not happen automatically. In many PPGIS

projects the reach has been quite limited serving only a small subset of

public (Schlossberg & Shuford, 2005).

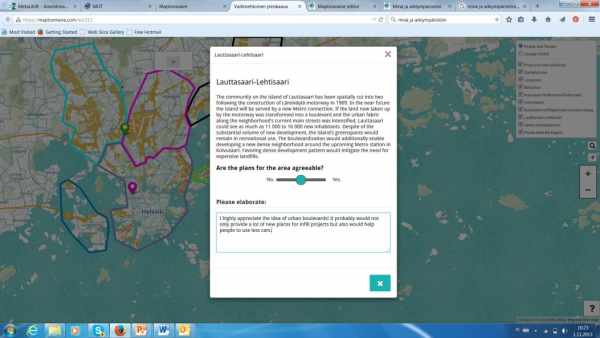

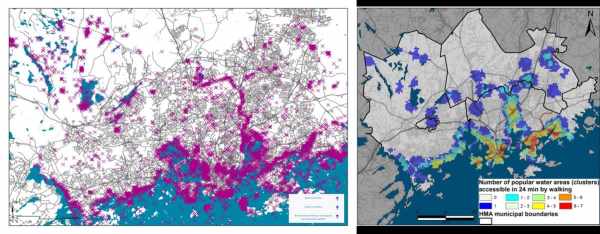

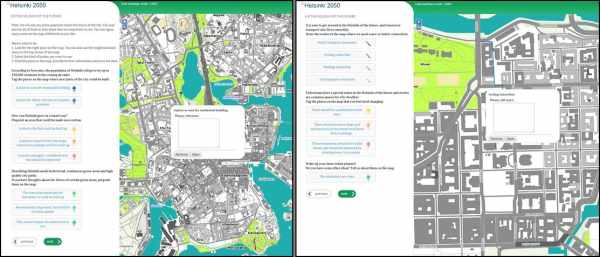

Figure 1: Some examples of PPGIS studies and planning practice

cases.

The SoftGIS methodology developed in Aalto University since 2005 is

an advanced example of PPGIS, which has been used already among over

30.000 Finns as well as in Japan, Australia, New Zealand, USA, Poland,

Portugal, Iran, Austria, Germany, Mexico and Brazil. SoftGIS is an

Internet-based public participation GIS (PPGIS) tool that allow the

locality-based study of human experiences and the transfer of this

knowledge into research and urban planning processes (Kahila & Kyttä

2009). Research themes studied with this methodology include for example

environmental childfriendliness, perceived urban safety and

accessibility of ecosystem services (see Figure 1). SoftGIS is grounded

in environmental psychology, but zooms closer into where exactly the

experiences take place [Kyttä, Broberg, & Kahila 2012].

SoftGIS

developed later to a commercialized Maptionnaire service that allow

anyone without any coding or GIS skills to create surveys and collect

and analyze data. The Maptionnaire tool will be introduced below.

2. INTRODUCING MAPTIONNAIRE – UNIQUE PPGIS TOOL FOR YOUR USE

Maptionnaire is a cloud service for creating and analysing map-based

questionnaires. Registering a test account and trying out the editor

tool is free of charge. Not long ago the creation and analysis of map

based questionnaires required considerable technological expertise.

However, with a commercial out-of-the-box cloud service Maptionnaire,

anyone can do a PPGIS study using no other tool than their web browser.

In addition to academic research, city planning departments,

consultancies and community engagement projects have been early adopters

of map based questionnaires. We believe that this is primarily because

there are higher-than-average amount of people with GIS expertise in

those fields. Location matters, whether you are studying suburban youth,

business travelling, real-estate management, infrastructure projects,

hiking in national parks, or shopping experiences.

2.1 Available maps

Maptionnaire includes a variety of maps. What base maps to use in a

questionnaire depends on the context. Often a survey needs to contain

more than one map allowing the respondent to choose the map layer of

choice. The map can represent

- the future, e.g. when asking opinions or ideas about alternative

town plans,

- the present, e.g. when studying the behaviour of people or their

mobility patterns, or

- the past, e.g. when collecting memories of elderly citizens.

Furthermore, the maps are not limited to the geography of large

areas. Small scale maps of indoor spaces such as schools, malls, or

airports make for interesting topics of research tool. Maptionnaire is

designed to work with essentially any digital map. This includes global

commercial providers like Bing, MapBox, and Google, as well as your own

WMS server that allows you to incorporate to Maptionnaire your own

map-files. In addition, if your map is a georeferenced image file but

you have no server of your own, it can be uploaded to our servers.

2.2.Types of map questions

Map questions can be constructed differently. Basically there are

two different approaches to asking questions on map:

- The respondent draws a point, line, or area on the map.

After drawing, she’s given a set of follow-up questions.

- The questionnaire itself includes interactive geometries on

the map. After clicking a geometry the respondent is given a set of

related questions.

Who is drawing on the map makes the fundamental

difference: either the creator or respondent of the questionnaire.

Maptionnaire supports both.

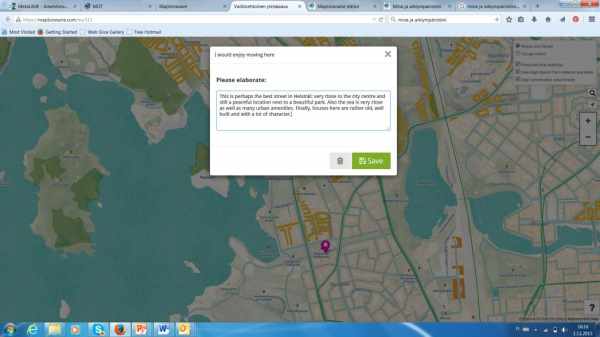

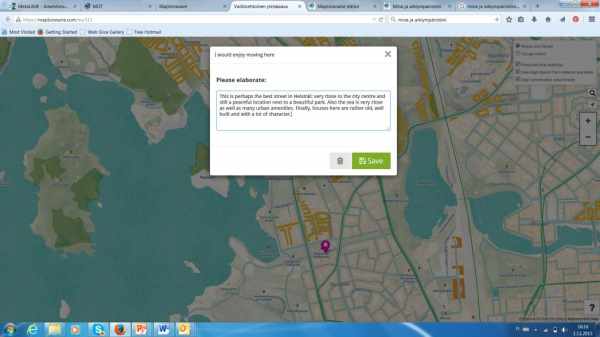

Let us take a map questionnaire focusing

on the housing preferences of urban dwellers and opinions about the

future development of a city as a simple running example in how to make

use of map in a survey and highlight the difference between the two

question types. In Figures 3 and 4 there are illustrations of both types

from the respondent’s point of view.

Figure 3 Placing a marker with

follow-up questions, respondent’s view.

Figure 4 Choosing predefined

areas with follow-up questions, respondent’s view.

2.3. Output data

and analysis of map data

In comparison to traditional survey data

where the data comes in table format in Maptionnaire service the data

includes also geocoordinates of the responses. The two main benefits of

having answers with coordinates are:

- Precision and lack of

ambiguity. Almost any verbal description of a location, let alone that

of a route or area, is open to a lot of interpretation. In contrast,

modern web maps and satellite imagery allow zooming so close that a

dutiful respondent is able to pinpoint each individual tree in her

neighbourhood.

- Efficiency of analysis

and visualization. GIS tools let us spot patterns in large sets of

location based data and infer meaningful results. In addition, it is

considerably easier to communicate our findings to other people with map

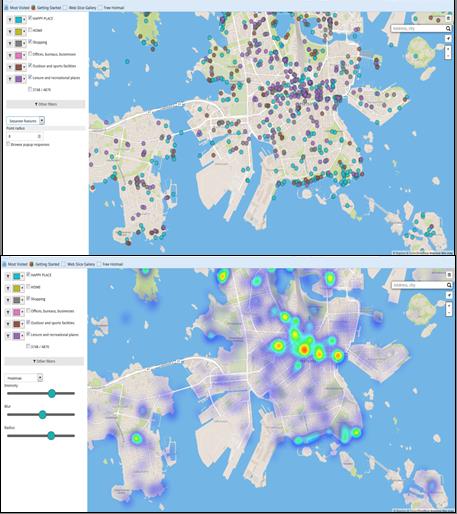

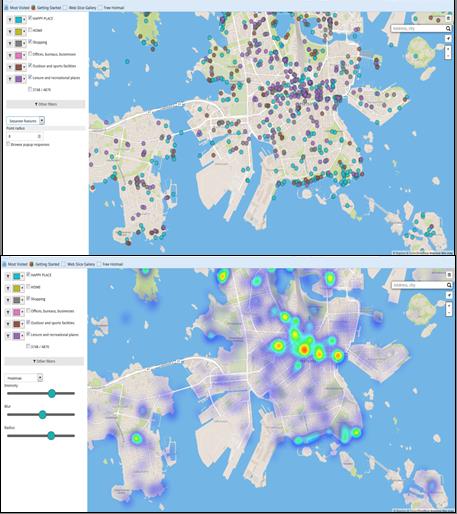

visualizations.In Figure 5 there are two screen captures

from the analysis tool of Maptionnaire. Above we are looking at an

individual point of response data. The colors stand for different

questions, e.g. “Where is the happy place, shopping place etc”. Below

there’s a heatmap of the same points where we see the concentration of

points.

Figure 5 Maptionnaire analysis tool. Separate points (above) and

heatmap (below).

Often it is convenient to share the responses with the public, such

that the respondents don’t feel their effort is vanishing into archives

never to opened again. The map responses can be published in two ways:

Directly within the questionnaire such that while answering, the

respondent is able to see what others have already said. It is also

possible to comment other people’s answers. The analysis tool can be

made public, in which case anyone can have access to the filtering,

search, browsing, and visualization functions of Maptionnaire.

2.4 Integration with conventional questionnaire forms

Even though well-suited for

participatory projects, Maptionnaire has its roots in scientific

research. As a consequence, it comes with a full-blown questionnaire

tool set. Semantic differentials, likert questions, and multiple choice

questions are included and integrated with the location based data. They

allow for powerful quantitative analysis and classification.

Suppose,

for example, that a questionnaire

- asks the respondent’s age,

- has a drawbutton “Where do you go to relax?”,

- and the

drawbutton has a follow-up question “What do you find there?” with

options “Friends”, “Time alone”, “Sports”, and “Art”.

The analysis

tool can then filter the response data according to all these variables,

and for example visualize places where 50-59-year-old respondents go to

do sports with friends. Please feel free to explore the Maptionnaire

editor in http://maptionnaire.com/.

3. THE USE OF PPGIS THROUGH DIFFERENT PHASES OF THE PLANNING

PROCESS

The participatory planning support system (PPSS) is a conceptual

approach that can be used to support planning practices with a set of

participation tools and actions (Kahila-Tani 2016). It emphasizes

participation as a solid and continuous part of the planning and

decision making system. The focus is on different forms of knowledge, on

the adaptation of new tools and on clarifying the ways in which PPGIS

tools can be more profoundly embedded in the planning process. PPSS

system leans on the knowledge-informed planning approach. This means (1)

openness to different forms of knowledge; (2) acceptance of the

conflicting perspectives of actors; (3) integration of different

participatory tools and practices more profoundly into the planning

process; and (4) sensitivity to local practices and context.

The following sections explore in detail the different phases of the

planning process and clarify the role of participation in each phase. We

will especially look at the ways how PPGIS tools can support the

knowledge creation during the different phases and give examples how

Maptionnaire has been used. As identified earlier, the challenge is to

embed the concepts, ideas and tools in everyday practices. As such, the

aim is to narrow this gap by indicating the locus of webGIS innovations

throughout the planning process.

3.1. Early initiation

In the early initiation phase of a planning process, the selection

of current problems and issues should be better supported by the

participation process. Currently this seldom happens in urban planning.

The initiation phase should acknowledge the role of informal knowledge

creation through public discussions supported by digital tools but also

the role of the more formal knowledge that different studies can evoke.

As such, this phase can often blur into the evaluation phase (see

below). Currently, the role of participants is often minimal in the

early initiation phase. Both decision makers, planning authorities and

interest groups such as resident unions and even individual residents

could have a say and eventually affect the process of problem

recognition leading to the initiation of a new planning process.

Unfortunately, this kind of more extensive form of participation

highlighting the plural nature of values held across society, rarely

occurs.

Our observations have revealed that PPGIS tools can prove useful

during this phase. They can be used for systematic and broad data

collection that provide a basis for identifying problems that could be

addressed in a planning project or positive qualities that should be

protected. So far, there is limited evidence to show that the collected

data would have significantly impacted the agenda setting phase or led

to the initiation of other projects. Various VGI tools that aim to

crowdsource knowledge voluntarily or argumentation maps that support

capacity building and trust suit also to the initiation phase. Here, the

target is rather to collect ideas and initiatives than high quality

evidence. Again, it is easier to collect ideas than to find new ways to

link these individual or collective ideas into a more formal process

that could, eventually, lead to initiation. This demands more

transparency and intense communication between planners, decision makers

and residents.

Case

example - Designing a campus for cycling and walking

The real estate

company Aalto University Properties wanted to know how people move

around the Otaniemi campus — and where transit could be improved. The

aim is to create a user-friendly campus, where cycling and walking would

be as smooth as possible. With a map questionnaire respondents marked

their daily routes and most important places of students and employees

of the campus. Additional pop up questions were asked about how these

places are reached, and where new amenities are needed. The respondents

gave numerous suggestions. The comprehensive survey data will be used in

the long term development of the campus area and its services.

3.2 Initiation

In initiation phase the project has been formalized. The empirical

findings from our studies support the involvement of the participants

during the initiation phase. Residents can act as information producers

as well as react to suggestions from other respondents. This way the

versatile experiential landscape can be laid out that emphasises even

the controversial views. The data gathering and analysis via PPGIS and

VGA can be supported with face-to-face collaboration and communication

to validate and supplement the data gathering. This multi-stream model

of different methods confirms the initiation and demands a more thorough

participatory approach.

Though our cases prove that PPGIS tools are capable of supporting

the early stages of the planning process well there is also evidence to

suggest that even though planners value data collection the actual use

of the data after this phase has not been as effective as it could be. A

number of reasons for this have been identified: (1) planners still lack

the necessary skills to analyse the data, (2) planners are more

interested in legitimating the participatory process by arranging

possibilities for participation than in ensuring that the actual data

collected is used effectively and (3) those charged with the data

gathering task are usually not responsible for the actual plan making

and thus are not that interested in precisely how the data is utilised.

Case Example –

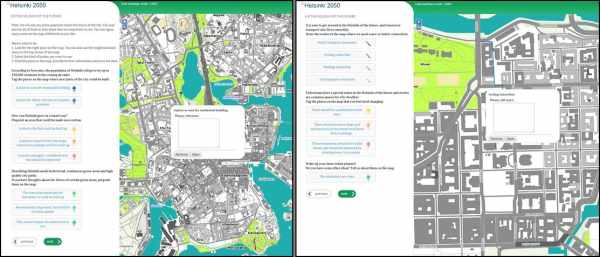

Thousands envisioned the Helsinki of the future

The city of Helsinki is drawing a new City plan, which will guide

the development of Finland’s capital until 2050. During the early phases

of the process city of Helsinki wanted to hear residents’ views with a

map-based questionnaire (Figure 6). Survey attracted almost 4000

respondents who made over 33 000 entries in the interactive city map.

The residents gave many suggestions for new building areas. They also

located urban nature spots they considered unique and worth protection.

“We got an excellent number of respondents and entries. The survey was a

success. Also, it was important for us to receive the analysis report

directly after the end of the survey, and the analysis tool for our

staff. I believe that the survey’s results will be used as a background

material for a wide range of future projects.” — Heikki Mäntymäki,

Communications Manager, City Planning Department

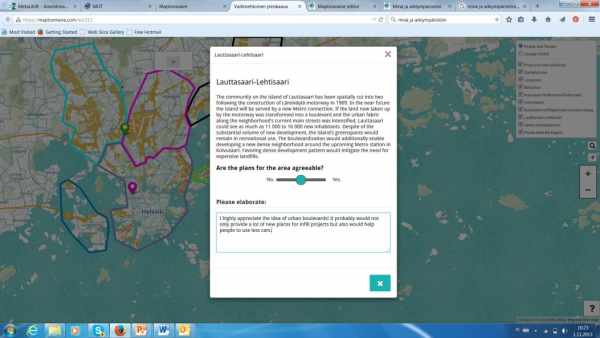

Figure 6 The Maptionnaire survey used in the

participatory process of Helsinki city plan 2050.

3.3 Formulation of alternatives

During the formulation of alternatives interaction between the

administrative level and the wider society often exists. Still, this

interaction is often organised through stable channels such as policy

networks. The formulation of the first drafts of the plan proposals is

normally, at least in Finland, held strictly among experts while lay

people are generally only able to comment on the proposals. Ideally, the

participants should be able to study and compare different alternatives

made by experts, affect the formulation of the alternatives and even

produce their own alternatives with the support of planners. Because

this planning phase concretizes the notions of a ‘good environment’ into

shaped plans that will then be negotiated and decided, inclusive

participation is essential to support the element of democracy.

In some of the completed PPGIS projects residents have been

allowed to evaluate different plan alternatives while the PPGIS allows

for a more dynamic visualisation of the plan proposals and enables

respondents to mark comments and opinions on a map. This phase could

become even more efficient if the alternatives outlined could support

transparency by highlighting how data collected previously have affected

plan proposals. This aim is, nevertheless, not simple to implement as it

is difficult to prove how such data has impacted the proposals.

Case

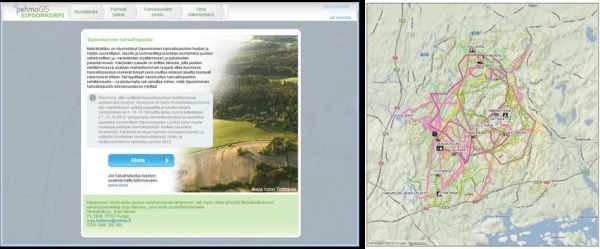

Example – Improving a national park with local insight

Finnish forestry organization Metsähallitus allowed the park users

to mark their favourite places (Figure 7). The majority thought that the

park needed both wild and recreational areas. The results influenced the

new maintenance and usage plan of the park, which separates the wild and

recreational areas. In addition, a PPGIS feedback service was designed

for alternative plans. The residents’ ideas and opinions were thus

included in the planning process on several stages.

“Maptionnaire is a

significant new service to complement the traditional hearing meetings.

It enables collecting opinions and wishes from wide stakeholder groups

and presenting them in graphic form. The data material is received in

GIS environment, which is a remarkable help. Therefore, it is ready to

use in map presentations and information systems.” — Senior Planning

Officer Arja Halinen, Metsähallitus

Figure 7 The survey used for

marking the favourite places and routes of park users (left) and the map

that summarizes the findings (right).

3.4 Decision making

The

final decision making phase remains in the realm of the responsible

institution where the decision is always preceded by a more or less

informal process of negotiated policy formation. This highlights the

importance of early stage participation in the planning process. Those

networks that shape the discussion are often long-established policy

networks with various interest groups. Whether existing policy networks

are really representative of a broad enough range of residents’ views

remains questionable.

Our observation indicate that only in a few of the projects

planners have been willing to use PPGIS tools during this phase. In

Finland, during this step all officially expressed opinions should

include personal data because planners are required to provide feedback

to every opinion. This procedure often delays the process as planners

can receive a significant number of opinions, each of which have to be

carefully studied. Understandably, planners are not eager to push the

use of the PPGIS tools during this phase as it would undoubtedly

increase still further the number of complaints. Experts are afraid of

information overflow where more information could lead to “further

confusion; obscuring, rather than clarifying the policy choices which

could otherwise be made more easily under conditions of relative

ignorance” (Young, Ashby, Boaz, & Grayson, 2002, 218).

3.5 Implementation

The implementation phase means the execution of the project through

the construction of the buildings, installing the infrastructure, or the

putting in place of some training or social programmes (Horelli, 2002).

The adoption of a programme does not guarantee that the action on the

ground will strictly follow policy makers’ aims and objectives.

Therefore participants should also be present during this phase, at

least through information. Empirical evidence does not, however,

currently support the use of PPGIS during this phase. Still, PPGIS would

be applicable to support the information process or perhaps to collect

feedback about the arrangements in the construction site.

3.6 Evaluation

The evaluation phase consists of

the assessment of the monitored data gathered throughout the project and

the evaluation of the changes in the physical and social structure.

Horelli (2002) emphasises an ongoing evaluation throughout the entire

planning cycle to better understand how participation has actually taken

place during the process. Thus, evaluation is not restricted only to a

particular stage in the policy cycle, but applied to the whole

policy-making process from different perspectives and different timing

(ex-ante, ex-post etc).

The research cases completed with the SoftGIS-tools support well the

ex-post evaluation which should play a more embedded practice in the

planning process. Evaluation could validate the effectiveness of public

participation by testing the generated quality of the process and the

quality of the received output and outcome. In reality, the actual

effectiveness of public participation remains hard to pinpoint as most

of the criteria discussed in literature are procedural rather than

substantive in that they relate to what makes for an effective process,

rather than how to measure effective outcomes ADDIN RW.CITE{{127

Rowe,Gene 2004}}(Rowe & Frewer, 2004). PPGIS tools offer a valuable way

to accomplish ex-ante or ex-post evaluation ADDIN RW.CITE{{63 Kyttä,M.

2012}}(Kyttä, 2012). The research cases concerning for example the

perceived quality of the living environment, environmental

childfriendliness or perceived safety can be viewed as ex-post/ex-ante

evaluation surveys. Here, the use of standardised queries would be

helpful to better enable comparison between data sets in different

places and cities.

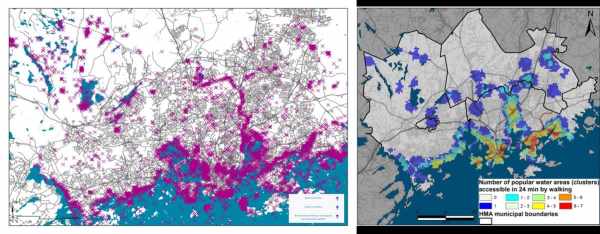

Case example -

Academic research on recreational water use

The researchers of Aalto University wanted to examine the

recreational use and experimental value of the water areas of the

Helsinki metropolitan area. A map survey asked the respondents to locate

activity spots and landscape values near bodies of water. The survey

reached over 2000 respondents. The results proved that the citizens

enjoy spending time near water. The city shores are an important escape

from everyday life.

“Mapping out the versatile nature of the best loved

shores is a great opportunity — we can combine the big picture with

detailed local knowledge, and qualitative information with location

analysis, which leads to new interpretations.” – Researcher, Jenni

Kuoppa, Aalto University

Figure 8 The activity spots by the water

identified by the respondents (left) and a map to show how many

important water areas are accessible by walking in different parts of

Helsinki metropolitan area.

3.7 Maintenance

The maintenance

phase means the transference of results and their nurturing into a

long-term perspective (Horelli, 2002). The residents’ role here can be

more passive turning them into commentators on the current state of the

environment. Regularly given feedback, such as e.g. Fix my street

-service, could have an important role in raising awareness of the

notifications made of the state of the living environment. Eventually

this or the former phase can feed into the understanding that connects

the process back to the problem definition stage completing the planning

process loop. The maintenance phase differs from the evaluation phase in

the way in which data is collected. In the evaluation phase it is

important to use random samples to validate the data while in the

maintenance phase data collection can occur on a more voluntary basis.

4. CONCLUSION

The aim of this paper was to introduce and go through the extensive

set of PPGIS practices studied in Finland and abroad by the SoftGIS team

in Aalto University. Long development work (2005-2015) of SoftGIS tools

and a commercialized service Maptionnaire have provided us insight how

research and urban planning practice can benefit of the use of these

tools. PPGIS tools are potential methods when a person needs to ask the

question “where”. It is powerful to allow local people to produce their

own maps expressing their personal experiences of their living

environment. Whereas in research this kind of data opens new

opportunities to study the person-environment fit in a novel way, in

urban planning the benefits are twofold. On one hand, planners embrace

this new information to support their knowledge-informed planning

practices. On the other, they can take the advantage of the tools as new

participatory mechanisms that consolidate the existing set of varying

participatory tools.

The Maptionnaire software and its multiple applications have

stimulated positive social change in the diverse fields of urban and

regional planning, environmental psychology, and natural resource

management, among others. How? The software was the first to

provide a user-friendly internet software platform allowing people to

identify and map their activities, experiences, values, preferences, and

other social attributes spatially, thus providing place-based data to

inform important social decisions about current and future land use. The

software also provides a platform for basic social research to better

understand how diverse populations, including children, interpret and

function in their physical environment. Historically, the “softGIS”

software contributed to what has been termed the “geospatial revolution”

over the last decade wherein the number of internet mapping software

applications has increased exponentially.

The empirical findings suggest that various PPGIS tools are

required to support different phases of the planning process and to

offer new ways to grasp residents’ views, experiences and opinions etc.

Further knowledge is, however, required from planning processes where

PPGIS tools are consistently used through different phases of the

project. It would also be interesting to study the data transformation

from raw data to planning proposals through the interpretation that

shapes the collective understanding.

To anchor the PPGIS tools and

location based user knowledge into the everyday routines of both the

residents and experts, not so many new tools and innovative concepts are

required. Rather, that challenge is to develop the existing planning

culture to become more open to versatile knowledge and to embed new

methods and ideas more profoundly into current practices. Our findings

highlight the important role played by the ‘super planners’ who are

willing to transform existing practices. As such, in order to overcome

these institutional barriers in the future we cannot continue to rest

alone on the shoulders of individual ‘super’ experts.

REFERENCES

Brown, G., & Kyttä, M. (2014). Key issues and

research priorities for public participation GIS (PPGIS): A synthesis

based on empirical research. Applied Geography, 46, 126-136.

Carver, S.,

Evans, A., Kingston, R., & Turton, I. (2001). Public participation, GIS,

and cyberdemocracy: Evaluating on-line spatial decision support systems.

Environment and Planning B, 28(6), 907-922.

Goodchild, M. F. (2007).

Citizens as sensors: The world of volunteered geography. GeoJournal,

69(4), 211-221.

Hall, G. B., Chipeniuk, R., Feick, R. D., Leahy, M. G.,

& Deparday, V. (2010). Community-based production of geographic

information using open source software and web 2.0. International

Journal of Geographical Information Science, 24(5), 761-781.

doi:10.1080/13658810903213288

Horelli, L. (2002). A methodology of

participatory planning. Handbook of Environmental Psychology, 607-628.

Kyttä, M. (2012). SoftGIS methods in planning evaluation. Evaluation for

Sustainability and Participation in Planning (pp. 334-353), Routledge.

Kyttä, M. Broberg, A. &

Kahila, M. (2012) Urban Structure Factors

Motivating Active Lifestyle among Children and Youth: A Case Study in

the City of Turku, Finland. American Journal of Health Promotion, Vol.

26, Number 5, e137 –e148.

Kahila, M. & Kyttä, M. (2009) SoftGIS as a

bridge builder in collaborative urban planning. In Geertman, S. &

Stillwell, J. (2009) eds. Planning Support Systems: Best Practices and

New Methods. Springer, pp. 389 – 411.

Kahila-Tani, M. (2016) Reshaping

the planning process using local experiences: Utilising PPGIS in

participatory urban planning. Aalto University publication series

DOCTORAL DISSERTATIONS, 223/2015

Rowe, G., & Frewer, L. J. (2004).

Evaluating public-participation exercises: A research agenda. Science,

Technology & Human Values, 29(4), 512-556. Schlossberg, M., & Shuford,

E. (2005). Delineating " public" and" participation" in PPGIS. URISA

Journal, 16(2), 15.

Sui, D., Elwood, S., & Goodchild, M. (2012).

Crowdsourcing geographic knowledge: Volunteered geographic information

(VGI) in theory and practice. Springer Science & Business Media.

Tulloch, D. L. (2008). Is VGI participation? From vernal pools to video

games. GeoJournal, 72(3-4), 161-171.

Young, K., Ashby, D., Boaz, A., & Grayson, L. (2002). Social science

and the evidence-based policy movement. Social Policy and Society,

1(03), 215-224.

CONTACTS

Maarit Kahila

Development director

Mapita Oy Kanavaranta 7 D 00160

Helsinki Finland

Tel. +358405626951

Email: maarit.kahila@mapita.fi

Web

site: https://maptionnaire.com/

|